Criminal Law in Three Easy Cases

one of which is made up

I like summaries, so this month I present my attempt to summarize criminal law as succinctly as possible. This summary is so succinct that it requires only three cases, none of which are typically taught in law school. One of them is a Supreme Court case, potentially the most important criminal case in US history. Another is a federal case from the district of New York, which was appealed to the Second Circuit (I'll explain a little about what that means). The third is totally made up. Let's start with that one.

Minnesota v. Smith

This case is not real. It's based on a fact-pattern proposed by a friend and former high school classmate, in jest, while I was in law school. Even as he laid out the problem, I realized he had inadvertently touched on some very deep principles in Anglo-American law. It goes like this:

Smith and Jones are pheasant hunters in upstate Minnesota. Really, this problem can take place anywhere, but I choose to set it in Minnesota to once again emphasize the importance of thinking jurisdictionally when analyzing the law. For the purposes of this fact-pattern, it can take place in your state...probably...but I hope it doesn't.

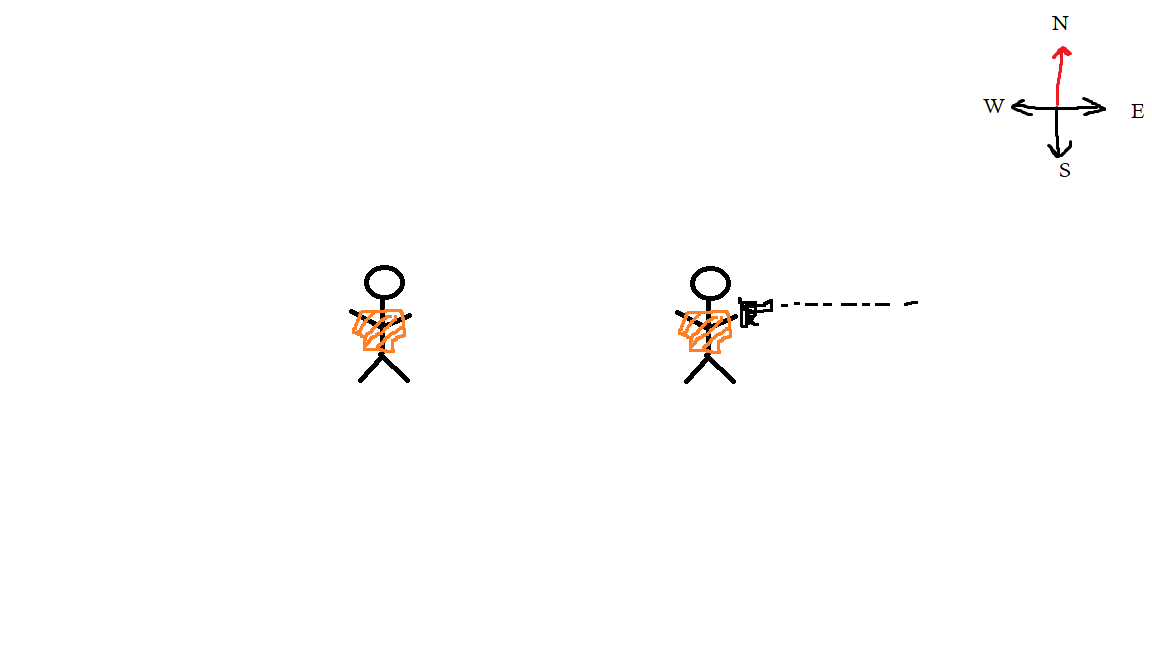

While on a hunt, Smith lags behind, and Jones marches ahead, in complete defiance of good sense and well-understood hunting practices. Both hike West to East for miles and miles, separated by only a few feet. Both carry pistols. Both are old friends.

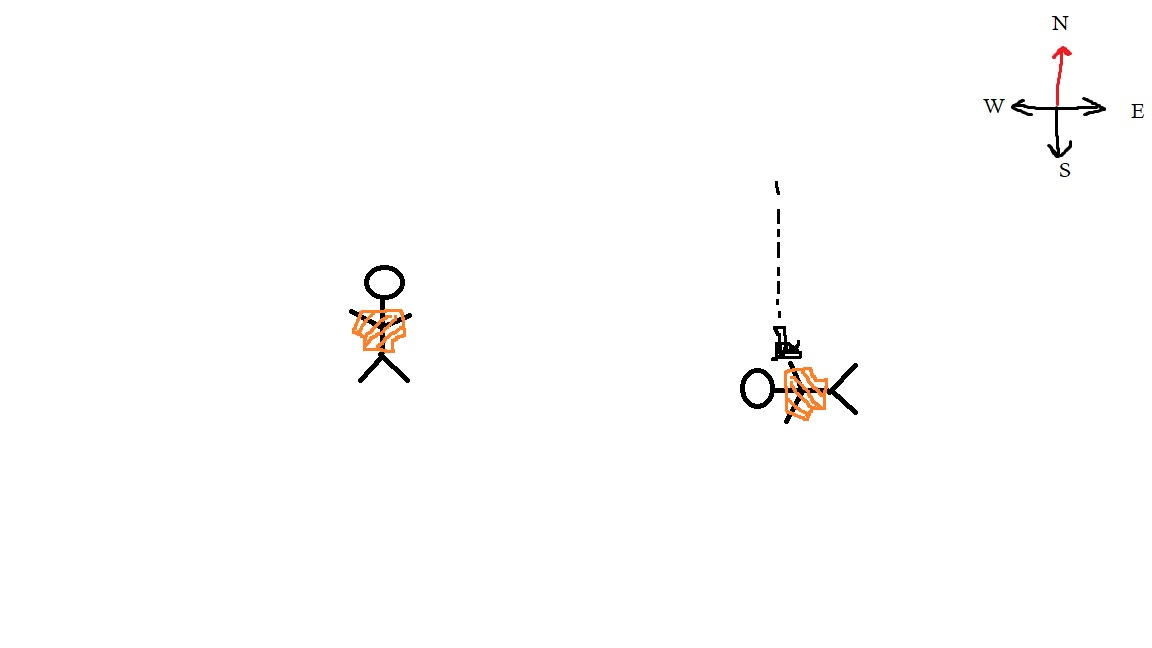

...and for some reason, whatever reason you want, dear reader, Jones stops, turns just a little to the North and discharges his pistol.

...there, that's it, that's the case.

Why is this interesting? Well, let's change the facts a little bit more. Instead of turning just a little to the North, Jones turns due North, and fires. Note that Jones is now firing 90 degrees from his original firing position.

Let's keep changing the facts. Now, instead of firing due north, Jones fires ever-so-slightly North-by-Northeast, perhaps 95 degrees from his firing position in the first hypothetical, and fires.

Let's keep changing the facts. Let's keep adding degrees to Jones' turn. Eventually, of course, he will have turned 180 degrees and discharged his shotgun right into Smith, killing him instantly (one assumes).

My friend asked, simply, the number of degrees one would need to add to Jones' turn for his act to constitute some crime. Murder? Manslaughter? Reckless discharge of a firearm?

Now, my friend was smart enough to appreciate that this was a deranged question, but in madness, there lies a particular kind of brilliance, because surely if Jones turned during that fateful expedition and fired his shotgun directly at Jones, this would constitute some kind of homicide. Is there an answer to question? Is this one of those Sorites paradox that philosophers jaw about until doomsday? Well, let's think jurisdictionally. What does Minnesota say about murder?

Out here, the Second Degree Murder statute says, inter alia: "whoever...causes the death of a human being with intent to effect the death of that person or another, but without premeditation...is guilty of murder in the second degree and may be sentenced to imprisonment for not more than 40 years"

The Second Degree Manslaughter statute says, in the relevant part: "whoever...by the person's culpable negligence whereby the person creates an unreasonable risk, and consciously takes chances of causing death or great bodily harm to another...is guilty of manslaughter in the second degree and may be sentenced to imprisonment for not more than ten years "

and in case you're curious, our attempt statute says: "Whoever, with intent to commit a crime, does an act which is a substantial step toward, and more than preparation for, the commission of the crime is guilty of an attempt to commit that crime"

Well...none of those really seem to answer the question. In fact they do, but to understand why, let's look at two more cases.

United States v. Morissette 342 U.S. 246

This is an underappreciated Supreme Court case, one where the unique facts of the case's litigation and appeal forced the Supreme Court to analyze criminal law on a basic, almost primal level. By sheer coincidence, it also concerns a hunting trip, though one with very different facts. It's a very colorful and readable case, and one that should be taught on day one of an introductory criminal law class. Sadly, the case is obscure, and even those who cite it don't really grapple with the facts.

Morissette was a hunter from Michigan who came up with a unique way to finance his hunting trips. He hunted on a sparsely inhabited woodland area of Michigan that overlapped with a government bombing range. At this range, the government practiced bombing techniques from aircraft that overflew the range and dropped dud bombs that exploded with a little "pop" and some smoke, enough to show where the bomb had landed. After a drill, the bomb casings were collected and piled together, left to rust in the Michigan rain. On his hunting trips, Morisette made a habit of harvesting these bomb casings, grabbing a few and throwing them in his truck. Upon his return to civilization, he sold them as scrap.

In December of 1948, Morissette took his haul back to Flint and sold the casings for $84. Critically, Morissette's taking of the shell casings, and his sale, were all done openly and with no subterfuge whatsoever. Nevertheless, Morisette found himself charged in the with one count of violating 18 U.S.C. 641. This statute punishes one who "embezzles, steals, purloins, or knowingly converts" government property. Here, "converts" basically means "takes for his own use."

Morissette's trial was a bit of an ordeal, and I genuinely feel sorry for everyone involved. Morissette testified you see, and openly admitted that he knew the origin of the scrap he sold. In fact, he even admitted he knew the scrap was taken from government land. Morisette merely argued that he did not know the property was still the government's. He believed it was abandoned (maybe it was).

The judge was quite unimpressed with Morissette, and as the trial came to a close. He admonished Morissette's lawyer as follows:

"[H]e took it because he thought it was abandoned and he knew he was on government property. . . . That is no defense. . . . I don't think anybody can have the defense they thought the property was abandoned on another man's piece of property....I will not permit you to show this man thought it was abandoned. . . . I hold in this case that there is no question of abandoned property."

He then instructed the jury: "If you believe the testimony of the government in this case, he intended to take it. . . . He had no right to take this property. . . . [A]nd it is no defense to claim that it was abandoned because it was on private property. . . . And I instruct you to this effect: that if this young man took this property (and he says he did), without any permission (he says he did), that was on the property of the United States Government (he says it was), that it was of the value of one cent or more (and evidently it was), that he is guilty of the offense charged here. If you believe the government, he is guilty. . . . The question on intent is whether or not he intended to take the property. He says he did. Therefore, if you believe either side, he is guilty."

Morissette's lawyer tried to argue that the taking, which everyone agreed had happened, had to be "felonious" to fall within the ambit of 18 U.S.C. 641. The judge rejected this argument: "that is presumed by his own act"

Morissette was, unsurprisingly, found guilty at the federal district court level. He appealed to the Sixth Circuit, which hears appeals from federal districts, including Michigan's. Morisette recieved no sympathy there, and further appealed his case to the United States Supreme Court. There, he met a sympathetic ear, for the highest court in the land found that a grave injusitce had been done.

In a unanimous opinion authored by Justice Jackson, the Supreme Court noted that "This would have remained a profoundly insignificant case to all except its immediate parties had it not been so tried and submitted to the jury as to raise questions both fundamental and far-reaching in federal criminal law..." they then began to explain the criminal law from the bottom up.

In the United States, all Criminal Law with a few irrelevant exceptions flows from statutes, passed by the legislature. Critically, criminal laws prohibit CONDUCT: the union of a criminal ACT with a criminal MINDSET or INTENT. Most criminal laws will spell out the precise act, and intent, that makes the actor culpable. In Morisette's case, the relevant statute prevented four nearly synonymous unions of action and intent, punishing one who "embezzles", "steals", "purloins", or "knowingly converts." I won't get mired down in what exactly "purloin" means in this context, sufficed to say that per the dictionary definition, one cannot "embezzle" or "steal" by accident. One CAN "convert" by accident, that is, one can "take for his own use" the property of another by accident: I can take my neighbor's lawnmower, believing it to be my own. I cannot, however, KNOWINGLY do so. And so, the Supreme Court found that Morisette could only be guilty of a violation of 18 U.S.C. 641's "conversion" prong if he KNEW he was taking the property of another.

But didn't he? Recall that Morisette took scrap metal from what he knew to be government land, scrap metal that he knew had been used by the government. It would be a fair assumption he knew the scrap to be government property. So what's the big deal?

There are No Fair Assumptions

The big deal is simply this: in the United States, one's culpable intent cannot be "presumed" by any entity except the jury...and certainly not by a judge. The Sixth Amendment guarantees everyone charged with a crime the right to a trial by a jury, and at that trial THE JURY, not the judge or the prosecutor, decides every fact of consequence, including what Morissette did or didn't know. This was true...and is still true, no matter how obvious or clear-cut the facts might be in a particular case. As the Supreme Court said: "Knowing conversion...requires more than knowledge that defendant was taking the property into his possession. He must have had knowledge of the facts, though not necessarily the law, that made the taking a conversion...presumptive intent has no place in this case. A conclusive presumption which testimony could not overthrow would effectively eliminate intent as an ingredient of the offense." The facts of Morissette are critical to understanding exactly how radical this assertion is: Morissette claimed he believed the property was abandoned, and could be freely taken by anyone. He had the right to have his claim adjudicated by a jury...this was so even though he took the scrap-metal at issue from a military bombing range ringed by signs that clearly said, in bright red letters "Danger -- Keep Out -- Bombing Range" (no really!). The Supreme Court put it rather succinctly in conclusion: " juries are not bound by what seems inescapable logic to judges."

Keeping this principle firmly in mind, we can dissolve an enormous number of legal complexities: did Kyle Rittenhouse intend to kill Joseph Rosenbaum? Did Alec Baldwin commit a crime when he pointed a gun at Halyna Hutchins? What if he lied about pulling the trigger of that gun? What if he didn't? Did Donald Trump commit a crime when he moved classified documents to Mar a Lago? Did Joe Biden commit the same crime when he placed a box of documents alongside his corvette? What if the police find a baggie of cocaine in my car, but I say a friend put it there and I didn't know about it? What if police find a baggie of cocaine inside me, but I say it belonged to a friend? These questions concern crimes. Crimes (almost always) require a particular culpable mindset. All we're generally asking in these hypotheticals is "can we safely assume defendant had the necessary intent?" And that answer to that question is always, always, always, "what would a jury assume unanimously, and beyond a reasonable doubt?" That of course necessarily depends on the specific facts of the case, as they are interpreted by the specific twelve people who sit on that jury. Arbitrary? yes. Unpredictable? certainly. The way it works? yes. Because of this ironclad rule, Morisette got a new trial, one where the jury, not a judge, decided what his intent must have been.

The imaginary case of Minnesota versus Smith is now quite easy to understand, though perhaps unsatisfying. At what angle does Smith's discharge of a firearm become criminal, say, attempted murder? The answer is whenever the jury that sits in judgment of him would agree beyond a reasonable doubt that Smith intended to shoot Jones. That could be ninety degrees, or one hundred...conversely, the jury might find Smith not guilty even if he turned a full one hundred and eighty degrees. The jury decides.

The Jury Doesn't Always Decide

One could stop reading and safely understand about ninety five percent of all criminal cases, which is remarkable, given that I've only discussed two cases so far (only one of which is real). I told you there was a third case. For this example, we will leave Minnesota and Michigan and proceed even farther East, to New York, where a cannibal cop waits to teach us an extra lesson on criminal intent.

The facts of United States v. Valle are even more remarkable that Morisette. NYPD officer Gilberto Valle led a double life: police officer by day, Dark Fetish Net member by night. For years, Valle communicated with a loose network of online friends. Together, they collectively fantasized about kidnapping, torturing, raping, and yes, eating, scores of women known personally to the network members. In these communications, Valle and his friends would construct elaborate plans for abducting their friends, neighbors, and wives. These plans were highly specific, detailing in full how the co-conspirators would obtain ropes and duct tape, pulleys and windowless vans, stun guns and knives, when and where they would kidnap their victims, even the prices they would accept for the sale or receipt of a particular victim. Valle even suggested he had access to a soundproof basement and a "human sized" rotisserie and oven, which the conspirators were welcome to use.

Naturally, when Valle's communications came to light, people were outraged and frightened, and when people are outraged and frightened, prosecutors tend to act. Federal prosecutors charged Valle with conspiracy to commit kidnapping and a violation of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (for looking up information regarding his victims using databases he had access to by virtue of being a police officer). This blog post will only describe the circumstances of the first charge, though the curious should definitely look up the equally-interesting odyssey of the second, which will likely be the subject of a later post.

To prosecutors, Valle's intent was clear. As to one victim, Valle told his associates "give me a week to watch her and get to know her routine, then we will agree on a date." As to another, Valle said "got her route to and from her job yesterday. I saw her go to work this morning too. It may be a tough abduction but give me a couple of more days." As to that same victim, one of Valle's associates replied "i want to rape her snuff her in different ways and use her as aprostitute till i tire of her than kill her". Valle's intent seems clear enough from these messages...presumptive even. For federal prosecutors, this was not a difficult case.

Valle's jury was duly instructed on the law concerning conspiracy and kidnapping. They were correctly told that in order to be guilty of participating in a criminal conspiracy, the objective of the conspiracy need not ever be realized. All that is necessary is that the defendant take some deliberate step in furtherance of the conspiracy, intending to help the conspiracy carry out its criminal purpose. Valle had done that, the prosecution argued, by communicating for years with at last three distinct individuals, offering to provide material support for planned acts of kidnapping, murder, and even cannibalism. That these acts never happened was irrelevant: these men made a definite plan to kidnap someone. Unlike Morisette, Valle's jury was properly instructed that it was up to them, and them alone, to decide whether Valle had the requisite intent to be guilty of conspiracy to commit kidnapping.

The jury found Valle guilty.

But Valle Appealed.

Among other things, Valle argued that the government had not presented sufficient evidence to prove his guilt, as to the conspiracy count. To prove Valle's intent, Valle argued, more was needed than a bunch of messages conveying Valle's wishes, hopes, or fantasies. A federal district court, surprisingly, agreed with Valle. The court noted that in the appropriate context, it was clear that essentially all of Valle's texts were pure fantasy: Valle had no access to a human sized rotisserie oven. His basement was not soundproofed. He did not follow his victims. He made no attempt to meet any conspirators in person. He did not even know their real names. He never even purchased the duct tape or ropes he promised. To the district court, Valle's communications were all acting, no more culpable than speaking a line in a play. The district court found that "under the unique circumstances of this extraordinary case, and for the reasons discussed in detail below, the Court concludes that the evidence offered by the Government at trial is not sufficient to demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt that Valle entered into a genuine agreement to kidnap a woman, or that he specifically intended to commit a kidnapping."

The government appealed to the 2nd Circuit, just as Morissette appealed to the 6th. The government got an even colder reception at the circuit-court level than they did at the district level. The opinion, by Judge Barrington Parker, is a masterpiece just as the Morissette decision was: "This is a case about the line between fantasy and criminal intent." Parker wrote. "Although it is increasingly challenging to identify that line in the Internet age, it still exists and it must be rationally discernable in order to ensure that a person's inclinations and fantasies are his own and beyond the reach of the government."

Both decisions in Valle stand for an important and oft-overlooked corollary to my above statement about criminal intent: sometimes, rarely but sometimes, the jury doesn't decide. Sometimes, even if the verdict is "guilty", the court can step in and find that, in the appropriate context, the government has not sufficiently proved their case. These cases are mirror images: Morissette stands for the proposition that the jury alone can presume guilt. Valle stands for the proposition that the judge can, in special cases, presume innocence (or perhaps more appropriately, find that the government has not properly demonstrated guilt).

Instances like Valle are ultra-rare in actual practice: they likely happen in less than one case in a thousand, and generally when there are "unique circumstances", as in Valle's case. Still, this potential is important to keep in mind even in the mine run of cases: there is a check on the jury's power to convict based on any fact-pattern they find culpable: the court must agree it demonstrates beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant committed the charged crime.

Is There Anything Else?

A lot, but it’s sophistry around the edges: how evidence gets presented to a jury, how the jury is instructed to make its decision, how the decision of the jury or the judge is appealed to some higher court…these are important in their own right, but passing trivialities to the concepts above: the jury decides whether the state has proven the elements of the offense beyond a reasonable doubt. Very often, the only question is one of intent, and intent is never a foregone conclusion. The jury decides whether that has been proven as well. If the court agrees, that’s often the end of the story.

Great post! I run into these issues basically all the time when I discuss law with Other People, and this is a really good quick survey of the topic. I'd heard about US v Valle before, but Morissette is fascinating in its own way.

There were a handful of typos, and I tried to clean them up here: https://pastebin.com/99knXAcA